28 Hubert Street, FRNT 1

New York, NY 10013

TEL: (US) 1-212-643-1985

EMAIL: info(at)cecartslink(dot)org

Interviews, editing and production by Simon Dove, CEC ArtsLink. Commissioned music by Shri. Transcripts abridged and edited by Anya Szykitka. Produced in partnership with Howlround Theater Commons. These podcasts are also available to listen to or download the transcripts at howlround.com.

Transcript abridged and edited by Anya Szykitka

Simon Dove:

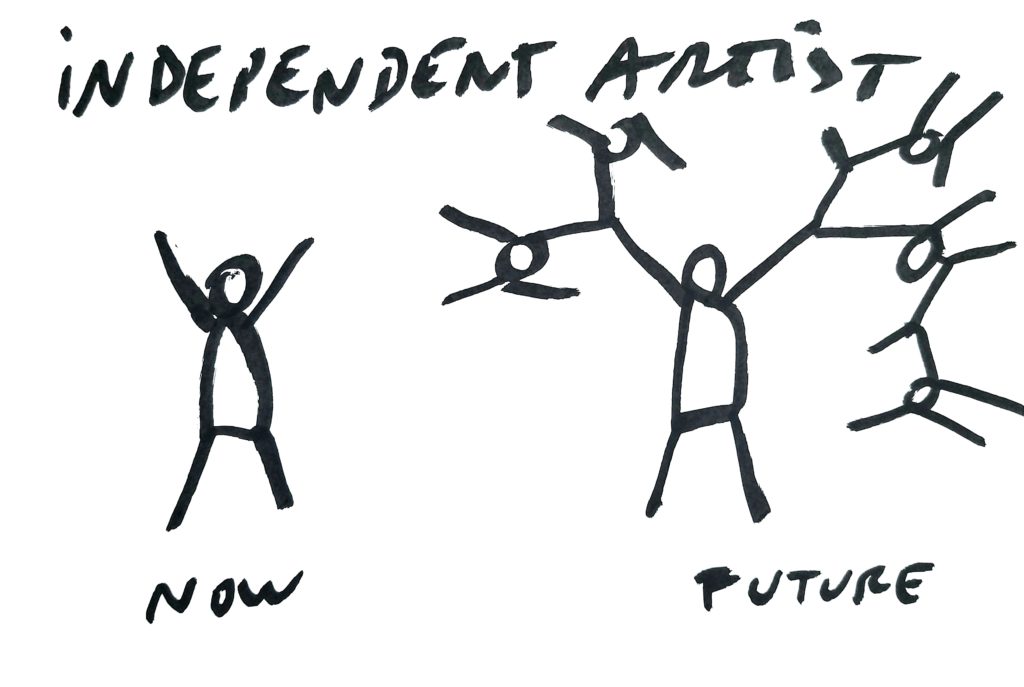

Hello, and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I’m the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. For this podcast series, we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Cannupa Hanska Luger, based in Santa Fe, U.S.A.

Cannupa Hanska Luger:

I’m Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, enrolled member of the three affiliated tribes (of Fort Berthold), from Dripping Earth Clan. I have a background in ceramics but do a lot of mixed media and installation using digital media, and basically any material that I have access to.

Models that we’ve used for the celebration and ultimately the commodification of art are being questioned today, maybe amplified through access to social media and communication. This sort of platform actually undermines the whole preservation model that most institutional spaces have been relying on for a few centuries. Our capacity to utilize the digital sphere opens up and challenges the way that art is related to. Art and culture are verbs, active and alive, in flux and changing.

As an indigenous person in the United States, I recognize that deep-time historical relationship to making your life beautiful; art is a byproduct of that. These are living examples of our culture and creative process. So as we move forward in time and have a much broader reach communicating with one another across what were initially geopolitical borders, conversations from a multitude of cultures that have been silenced or ignored throughout the last couple of hundred years are actually communicating with one another and bypassing the center for culture share, which would be your museum or gallery or market, even, of information.

With access to that amount of communication, technology, and inspiration, we can actively participate in the maintenance and adaptation of our own cultures through ideas drawn from the lands of each indigenous community across the globe. My own practice, having a background in ceramics, there is an emphasis on this historical object that can exist in defiance of entropy for a long time. So I wrestle with the idea, am I making these objects, or are the objects actually making me?

Going from three-dimensional, hard ceramic forms is informing me on how to create more performative acts, which exist in the fourth dimension, with time. Film and digital media allow me to create a record of those experiences that can then be shared on a global network versus my immediate community. All of that is in response to this umbrella of consumerist capitalist influence that also breeds voyeurism and narcissism. How do you subvert these two very toxic traits? Using social media as a platform for people to participate in the creation of work, and/or celebrating and sharing work that emphasizes an alternative way to engage with your environment, to see your land with reverence rather than just resource.

I believe from my own experience, how you amplify and lift each other up in certain ways have existed for a long time, that there are grassroots models of how to organize, to communicate. You see a lot of artists and artwork and culture bearers existing on the same platforms as say a resistance or protest narrative. But that is the same kind of functioning model that generates a potential alliance and intersection of peoples’ varied experiences. They become a tightly woven network of communication, ask, and support. So tightly woven, it’s harder to fall through that network once you’re part of it, whereas the larger industrial, colonial, empirical model is a loosely woven network, and many people fall through.

A grassroots effort to do so actually generates more of a connection to your immediate community. And that, as a model to participate in, also influences the way you interact with your immediate family, roles in the household. Then beyond that, within the neighborhood, community, environment, there’s a reverberating network of care, a model that had worked for tens of thousands of years and was deemed primitive at some point in history. But we are quickly recognizing that it is a more holistic way to engage with community that’s not a code word for brown and black people.

The effort to dismantle existing institutional spaces may be wasted because they are brick and mortar. We’ll never understand what a decolonial experience is because their core existence is the transformation and the annexing of land and space. So these spaces, I don’t know if they can ever become truly a decolonial experience. However, the effort to decolonize feels like important work. But I’m more interested in how we re-indigenize our way of thinking that has a root in its relationship to space and land, and consider that the creation of something else is the best way to destroy something that’s obsolete. I’m no longer in a demolition process but rather can help to generate something that will make it obsolete.

That’s what I’m hoping to see but also don’t have any expectation of experiencing that in my immediate lifetime. We are sowing seeds. The fruit is for future generations. I may never live in the world that I imagine, but I am happy to die trying to create it. And the notion of that sort of effort, of pushing this envelope slowly forward, is encouraging enough for me to continue.

There is no effort made now that isn’t going to be worth something a generation from now. And I’m happy that there is a level of disorganization in this learning curve process that develops a much cleaner communal idea of what the future is going to look like. Especially when we’re dealing with institutional practices based on order. I don’t think you can use order to dismantle that. The chaos of trying to understand and trying many different modes to dismantle and/or build and establish a new paradigm are equally valid. I’m happy that I can work in my own independent way and understand that I’m not alone in that effort, that there are many, from many different angles, coming in and converging on what we want as representation of not only ourselves, but our community and how we want to share culture and art with one another.

Whatever I’m doing is not necessarily sustainable. It’s in response to the environment that I live in, but as all of that starts to shift and change, I have no idea where my next structural support system will come from, and I don’t think it will be from the one that I’m developing presently. It’ll be some other underlying network, whether that’s a farmer’s union, an imprisoned population, a homeless community. I don’t know which one will end up being the most beneficial, but I’m happy to apply a variety of ideas and know that others are applying a variety of ideas, and that down the road one will be praised and the other will be abolished, and whatever survives that crucible will be what we end up kind of utilizing. What works for one region doesn’t necessarily work for another, so I would be interested in the multiplicity of possibilities rather than trying to find a unified theory for us.

Because I cannot exist in the future that I imagined, I have been of late obsessively developing work that is indigenous futurism, science fiction, ideas and forms emphasizing ancestral knowledge, applying it through new material and imagining what a potential culture and community could look like.

I can imagine, and have even seen, life growing in Superfund sites and areas decimated through extractive industry and pollution, and somehow, some way, I could make a go at it here. Let’s look at our more-than-human kinships, our relationships, to our environment and space. Then instead of looking at it as a potential resource, let’s look at it with reverence and understand that there is an important wealth of knowledge that a blade of grass growing through a crack in the concrete can share with you, if you look at it in the right light and perspective. You realize what we call urban spaces is a front line trying to annihilate life as it’s continuously dismantling the infrastructures we’ve created, breaking it down and turning it into a spring for growth.

I see it in our most polluted areas, our most economically despaired areas, and in our wealthiest areas as well. It finds a way to generate growth. And what I tried to do with my work, what I’m interested in is, how do you unshackle this notion of humans versus nature? How do you reestablish a kinship and a relationship to your own environment so that you see yourself as an extension of it, rather than something separate?

As we talk about environmental efforts and things like that, we need to be real honest about what we’re talking about, that the ship is going to keep moving, the planet will keep revolving. It was happy a ball of flame, it was happy covered in ocean water. As a highly adaptable species, why have we forced nature to adapt to us when we can adapt to just about any climate? Every diverse culture you’ve seen in history books and museums and everything, every phenotype, all were developed out of adaptation to place.

My optimism is based on what I have seen as a living thing on this planet. I get to share one of the most complex, complicated, incredible powers and forces at play, and somehow just by being brought into this space, I am a participant. I have a direct line to the sun we circle, the moon that affects our tides. There are so many forces at play, but they are not against you if you understand you are a part of it.

We’re not guaranteeing ease. Difficultness is what makes us better at living. Challenge is what hardens our body and hones our senses. My optimism comes of sheer awe of being anything at all. I’m also a father: what would I do with pessimism or defeatism raising two young boys? I’m only borrowing this place from them. We are only borrowing our world and our life and our experience from future generations. It’s about time we start acting accordingly. Dramatic pause.

I have a hard time placing myself in the position as artist. Primarily our function in society is social engineering. We build bridges from our perspective to another, and it’s not necessarily that we ask people to trust the construction of that bridge, but that its creation allows them the possibility of crossing, wayfinding and pathfinding.

Linking artists together is incredibly important and is also what naturally happens to the creation of any sort of object or work. Not only can you communicate with living peers, but you can communicate with the dead and unborn. That’s what we try to do, we are talking. This social engineering is an impossible architecture because it has the capacity to span time and space. Any interaction that allows us to communicate with our present peers, also those geographical, social, and economic experiences, become pillars of bridge building. I can span the gap if I know where it’s going to land, and working with artists from other regions and communities allows you to understand where your span is going to reach. Possibly we’re both building in the same direction.

It’s important to retain some sort of understanding and relationship to the place that you belong to and the land that you belong to and build these paths and bridges for those who want to push the edge of that. And somewhere along that span, people may build a whole culture and civilization that will span in another direction. And it’s their responsibility, their artists, their culture that will then generate an even tighter network of communication, so I don’t think we do build them necessarily for us. We can cross them, we can go and meet, but that’s not why they’re built. They’re built for the public, for the community, the people at large, who aren’t necessarily doing that sort of thing, but it creates a platform for people to meet somewhere along that path. I’m just building bridges, man.

Simon Dove:

You have been listening to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and post-production is by me, Simon Dove, Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows, supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Simon Dove:

Hello and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I’m the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. For this podcast series, we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Qondiswa James, based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Qondiswa James:

My name is Qondiswa James. I’m a cultural worker living and working in Cape Town, South Africa. My mediums are mostly performance. I’m interested in writing-knowledge-theory as it relates to activism and solidarity building. But I also do whatever comes my way to make bread, essentially, but also to keep challenging myself, a multi-disciplinary kind of person. I’ve even started to work in collage as a medium. I’ve done installation works. I act, write, do voice, multiple things.

I’m lucky to have a calling to something that I can live doing: I can make money, eat, manage to hustle. This hustle can be something I put towards my purpose. How to affect the world, build a better world. I’m lucky in that all these things aligned. But there are particular avenues or choices you make around which kinds of work to take, or basically, just the choice to take any kind of work, right? Which is about bread, because we are in the arts, and it’s not like I can be a freelancer. I haven’t had permanent employment in two or three years. So sometimes in a month, even though your rent is paid, you have nothing. Something just pops up: I will go to the meat-market audition and try and get that ad to push some corporation’s message that I don’t believe in. This is the complexity of living here now.

There is already preexisting mutual aid in the community of cultural workers. We find ways to support each other. Then we try to hold doors open for each other or introduce each other to new avenues of access. But of course it’s complicated. And in South Africa it’s historical, in a class race kind of way, and how class and race has been zoned, spatially in geography and urban centers, and how that eventually plays out as access, right? And then how people navigate and negotiate that.

I come from a theater tradition, mostly a theater maker. It has workshopping as its frame, its reference. South African theater, because of protest theater and its history . . . people weren’t being taught in European theater, the literary traditions that were being imported, and were finding it from their bodies and traditional practices of virality and improvisation and ritual. Workshopping for protesting became the thing, kind of agitprop theater.

The student movement is a moment in my political becoming, how I come into the network of so-called political people, people interested in politics here in Cape Town. I can reach out to them and say, Hey, I either have very little, or I have got real money, which is actually better when you can share proper money! Or you can say, I have very little, and I have an idea about something. Whether it’s creating a piece that can then tour to schools, right? And can we do educational and activist work, but also give people bread? Or whether it’s exhibitions or events or actual plays, and short films. Whether it’s responding to digital media, like the time we’re in now, right? Everything has to be online, otherwise there’s honestly no point. Every single project that I make now, that other people in my community make—theater performance, performance arts—you have to conceptualize its existing on a digital platform.

There is improvisation and devising and workshopping in how people, especially working people, are forced to live their lives, right? Hand to mouth precarity that we all experience, to greater or lesser extent. This improvisation that we’re used to, this hustle, is something that we can transplant, that we have already. The network does work. It’s about continuing to trust it. The thing with the network is that there’s no money. That’s the thing that’s really difficult. We are plugged into each other. We do reach out to each other. I do anyway. And I encourage other people to do it. Sometimes there are things I’m doing for bread, and not doing for bread. Sometimes I’m doing it to support other people getting bread. And sometimes people do that for me.

The way that funding structures are, the government, for example right now there is an open call for the National Arts Council. Anyone can apply, individuals, et cetera. People do get this money. So don’t knock where it’s working. But, I think the NAC, every three years gives what they call flagship funding. It’s almost guaranteed that they will give the institutions, which have already most monopolized the funders, private funders, et cetera, will give them all the money, then trust those institutions to disseminate the money by creating employment.

The government should be disseminating that money evenly amongst everybody. The problem is that the disseminating happens at the top and there is no transparency. The structure is dying. It is becoming derelict; as an abandoned house collapses bits of green starts to come out of the cracks. That’s the only thing I’m interested in. The structure’s a carcass, a dead thing. But we’re not ready. We’re not organized. Isn’t that the problem, the world over? In every sphere of politics or activity, we’re waiting for opportune moments to become organized as opposed to becoming organized. Because this infrastructure of the independent network, like I said, has existed since apartheid and resistance and the culture of protest, art protest, et cetera.

Parts of that even got actually formalized because of the new dispensation. So in a sense, maybe there’s been a demobilization. There’s also a kind of complacency, because people are able to wiggle enough around, even if it’s uncomfortably, to make it work, and that if you kick up a fuss, it’s not worth it. This person, Mamela Nyamza, she’s kind of famous, an incredible performance artist, dancer from South Africa. She was away from South Africa for a couple of years, maybe five to 10 years. Because you have to do your art here, become relatively known in your network, not in South Africa, just in your network.

Then your network opens an international portal for you. Then in order to make it solidify, you have to go and live somewhere else, Germany, France, America, wherever, or Canada, for five to 10 years. Then you come back and can get a job at a big institution, perhaps.

So she comes back, gets a job at the State Theatre as artistic director. She gets three years; I don’t know how long she was there. Even less, two years, she gets fired because Mamela Nyamza is a feminist and kicks up a fuss. Sometimes it doesn’t seem worth it. Even when you’re inside and you’re, like, Let’s change it! And you’re more like, Oh! I finally made it. I can relax. The further away you get from where you started, and the less visible those struggles become, the more comfortable you are, the more impossible it becomes to imagine the struggle again.

So we have created an alternative and are making do. It’s just terribly underfunded. And because of that underfunded-ness, it feels like there is no point putting much effort into formalizing it in any way. But there’s definitely something there, otherwise we’d be starving or everybody would be part-time baking cakes. Which by the way, in some of the research for the podcasts that I’ve been doing, a lot of people are baking cakes, like art makers, art facilitators.

You go to school, become a theater maker, then leave school. And you realize that the industry’s oversaturated with theater makers and very few people are going to make it, underfunded, et cetera.

So then you say, Okay, I’m going to become an arts facilitator. Even that’s a negotiation. Then hard times hit, right? That arts facilitation, freelancing gig runs out. You can’t find anything else. A pandemic hits. Now you find yourself baking cakes. Which is fine because you love baking cakes, but you’re a cake baker, you know? My lecturer used to say, if you are a waitress and I come to you, you’re serving me, and I say, Hey friend, what do you do? And you tell me you’re an actor. You’re not an actor. You’re a waitress. You’re an actor if you are acting, pounding the streets, doing the auditions, actually making it into plays, into ads, into series, into whatever, being an actor. Otherwise, you’re baking cakes.

There’s not enough support for this thing that already exists. And oftentimes you have to do something else entirely, which is why at the very beginning, I say that I am lucky. And the way that I am lucky, just to be clear, is because I have grown up in a particular environment. Even though I grew up in a working community, I’ve grown up middle class. I went to private school with white people all my life. The mentality you get taught, you believe it, that you can do anything, the world is your oyster, et cetera. They were teaching white people, and I am just there listening. So I’m also going to sponge it up.

And some people are not even baking cakes, you know? Some are sitting at home drinking alcohol, people that I went to school with who have given up. It just seems difficult: to buy the data you need to log on to the meeting, or to find a 50 rand; or borrowing 20 rand, which is like, I don’t know, $1.05, to be able to go to a meeting and come back. Even those four meetings are not going to get you paid, not getting your bread and your family and whatever your responsibilities are breathing down your neck. The dynamics are very complicated. But there is an alternative, and people have lost faith in the existing organizations.

What we’re really interested in is a multi-disciplinary arts school, which begins as a tertiary alternative—not just theater, not just fine art, not just whatever, all of these things—which has got at its frame a political activist lens, that has a food garden network, on-the-campus housing for people who need it. A completely self-sustaining space, but which is educational, creative towards getting free. But again, the demobilization people are not ready. And artists, we’re not sharp like that anymore. Some of us were becoming sharp, have retained a sharpness, but we’re not sharp like that, where it’s art and politics and we are going to rise up in exactly the same way that other people rise up. But more so because we can communicate and message in more effective ways. It’s like moving through treacle, thick, thick mud.

It’s about how we choose to take on the work of connecting our art to people directly. Without that direct and strong relationship between . . . which actually existed in apartheid, especially the latter years of apartheid, the seventies, eighties, and early nineties: art was a core part of the movement, of people’s everyday existence. Even Unam, who’s working at the shop right, and can be found with a little poster in her bag. The way that things like that were moving. There’s been an active demobilization.

The South African landscape will become such that we have no choice but to make things happen. It’s not going to look pretty or anything like that. That’s why I don’t want to speak about it as optimism. People were so disgruntled, so unhappy. We’re talking about it more and more, the ruptures are becoming bigger, more inexcusable. Now they’re dividing communities in particular ways, people the state is trying to govern. Things are changing. Since we’ve been on this Future Fellows, I’ve been really embracing the future in the present. In general, I’m not about futures. I’m about now. Now. The future is interesting and imagining it is interesting. Imagination and building it is interesting, but now.

Simon Dove:

You have been listening to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and post-production is by me, Simon Dove, Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows, supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Simon Dove:

Hello, and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I’m the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. And for this podcast series we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Marat Raiymkulov and Malika Umarova, also known as Art Group 705, based in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

Malika Umarova:

I’m the first to start. My name is Malika. I’m an artist, although I do not have professional artistic training. I come from medicine and used to work as a doctor, but now I’m part of Theater 705; it’s a collective. We are based in Bishkek and are making something in between visual art and theater, something between or a connection between them.

I also have my personal artistic practice and also work with children as art teacher. That’s brief, and I should pass to Marat.

Marat Raiymkulov:

My name is Marat. I work as a physicist, and also as artist. Sometimes I’m invited as an actor to theater plays or performances. I’m participating in Art Group 705 since the very beginning, and was going with the Art Group through several crises.

We live through these crises and search for approaches to go through them. Considering the school part of my life, I was witnessing how USSR was collapsing, and so-called post-Soviet time was coming. I had a chance to watch how other systems were coming. This became the source for me to turn to art, which gives rare tools to analyze social, emotional, existential processes.

After the collapse of Soviet system, nothing is yet organized, not yet stable, and we were thrown into unclear, not-so-easy-to-understand, to comprehend, situation. Art allows to search your ways in this life.

We are based in Bishkek, capital city of Kyrgyzstan. We used to be part of Soviet Union. The center of Soviet system was Moscow, not Bishkek, and later, after gaining independence, the city was renamed; used to be called Frunze, then it became Bishkek. Bishkek is often shaken by revolutions.

We’ve three revolutions, coups d’état, whatever you call it. Sometimes it’s parliamentary country, sometimes totalitarian country. It’s constant shaking, like a mirror of Central Asia. And what we do in Bishkek is, as I said, an exploration, study research of our society, our history, and an attempt to collect yourself, put yourself together.

Malika:

Who is our community? First of all, those that are closer to us, these are our artists. Our art community is not shaped, not based on any big or any kinds of artistic institutions. It’s totally organized on the enthusiasm of several people. Part of our work is, as Marat says, put yourself together to just be artists, to make art.

That’s how these artistic communities are nurtured and staying alive, surviving, and how maybe new artists and audience can emerge. I come from medical field and became interested in art exactly this way, being involved into Art Group 705, and now in Theater 705. It happened to many other people who were joining.

The art community is shaped through this working together, joining each other for a period of time and keeping these friendship connections. But also of course, there’s another community: the audience. Our principal theaters are very strange places. There’s a basic understanding, in our people, that one needs to go to the theater; this is art, high art, and one needs to go.

But people do not go because it’s simply boring. It’s not about them. It’s shaped as, this is how art should look, but is not about them. For these people to become community-involved, interested in art, they need to recognize themselves and their modernity, or nowadays life, in these works, in the theater, in the performances, in any kind of events they can visit and see and touch.

Working with them is talking about them, is talking about us. That brings this connection, and they have this feeling of recognition in our theater place. We’re becoming very small, totally based on ourselves, but city theater. Because they come and say, oh, this is about us. And even we’re trying to make it more in Kyrgyz language, and they’re saying even in the language, yes.

Marat:

I agree with Malika. We approached collectivity in a different way, not as the union of artists—a heritage of Soviet times—who are joining each other under the same manifesto. Our collective looks more like a theater where people join each other to bring something different, more than just the sum of the bodies.

This is a collective body. This is one of the basic principles of theater, different from contemporary art, where you can exist in various mediums, in various spaces. But theater exists exactly in its own community. This is harder because you cannot go and live, go to New York or the Pacific Ocean, because theater is people, community, and you have to talk to them, see them, spend time with them.

Pandemic did sharpen relationships, and the crisis was, on the one hand, due to pandemic. But on the other hand, this was political crisis in Bishkek when this third revolution happened. And it showed us that for our authorities, priority is economics.

There are many questions also about the legitimacy of this authority, but we’re not talking about that now. Money and big, rich houses and power, this is what is important in this time, in this political crisis. In crisis times such as today, art becomes even more important because it is necessary to understand what is happening, what words you can use to describe it, and what emotions you have about it. Huge catastrophe is happening, but it might stay without words.

What we can catch, we try to reflect in our performances and exhibitions and theater. It’s important to find what is happening to us.

Malika:

Many people are leaving the country in search for a better life. Partly due to the reason that Marat was talking about: when you cannot find words to describe, when he cannot find words that he wants to hear. Also talking today to some people, they were saying that it’s hard for them to find people for work, for jobs, because good, young, clever people are leaving, and this year even more intensely than usually. I’m worried about that.

When people from our community make a choice to stay, or they want to, when you hear the words you need, or something about you, you receive energy, and this energy helps you stay here and hope for something for your life. It proves there is some reason to still be here, some reason to think: this is my city, these are my people.

Marat:

Again, I agree with Malika. There is a tendency towards one-dimensional man. There is a very direct, linear form of life where it’s important only to stay alive economically, and that’s all.

But while you solve this question, ecology is suffering, institutions are worsening, and it’s not less important. Where do people see themselves and their children tomorrow, in future? Future is now. When we work on an artistic network, join forces with artists to create performance, create a theater play, you see that there are very few alternative spaces, alternative ways where and when you can do this work.

It’s important to share your knowledge, not like in the news, where knowledge does not cover our life, events from our life. You need analytics to decide what to do in future, and future is now. Only when we join each other, we create this alternative. Of course, if we succeed, the joy and the energy we have from this.

Today, we can see possible alternatives. Last year was so complicated that we were not sure whether to continue things we started long ago. Also, to make performance is quite complicated, and when you put it within social distance, it’s super complicated, and it’s the death of theater. But we continued and are doing it because we felt that people want it.

Today they are ready to support this. There is emerging understanding that art can be a tool of transformation and comprehension, unlike news and social networks. Art is able to talk more in complexity, more accurately, more interestingly. This understanding brought people to readiness, to support physically, to collaborate. This understanding for theater, for art, is of first importance, people and their attitude, their wish for such activities to continue.

And second, about institutions, this is about, for example, donorship, but not only, all art institutions. Never to hurry, to take time. Art institutions often are either hurrying or making boring things. But pause is a basic principle of learning, not to be limited by timeline, deadline, etcetera, to be in the process, to be able to refer, to return to your previous ideas and material and work and rework it.

And the third: it’s important for artists, themselves, to support each other. They do it, not all of them, but basically they do it. Our Central Asian community is based on the principle of helping each other. That is what we want to take from now into the future.

Malika:

Yesterday, I was thinking about this: not hurrying and making real things, instead of making something according to someone’s schedule.

Sometimes I’m worried and pessimistic, and sometimes quite optimistic, but majorly, I have optimism. Because I’ve seen all history of our group and the changes that we experienced, and I see new people coming to theater place, and this is what Marat was telling, that people are coming to understand that this art is important.

Also because of support from some friends, when there are times you think no one can understand what you’re doing, if there’s a group of people who recognize and support it, they keep you ongoing and make you an artist. I’m optimistic because of some people.

Marat:

Yesterday I was watching a movie. I did not have a chance to find out what this movie was, the name of it, but I liked it. And I liked, most of all, one character. This movie is telling about a spaceship lost in the universe, in cosmos, in space. And people are not aware of it. They don’t know it yet, that they are lost and will never come back.

There’s a woman, an astrophysicist and she knows we are already lost in space. For me, it’s twice as interesting, because this spaceship is the image of Bishkek together with COVID pandemic and political situation.

Also, as a physicist I understand that physics is working with catastrophes. For example, big explosion and emerging of the world, the universe, isn’t it a catastrophe? Each time when physics explores these catastrophes, this is wow. In this sense, catastrophes or crises that we go through, that we experience, in a way, this is cool. On their own, they are unique, and our task is to understand that in these catastrophes, accumulated is our previous experience, but also our future.

The idea is to embrace in these crises, all the most optimistic things, and leave behind all the pessimistic things, which need to be collected in art. Thus it will be interested to read all about it after 50 or 60 years.

Marat:

Marat was provoked by the words about the spaceship. We did not have a chance to watch this movie till the end. It seems that the ship found a way to return home. But this moment before finding the way is the most complicated. Crisis attracts crisis, and this attracts panic, so does the COVID. We might have not yet understood everything about it. The spaceship needs to find the way, but first to free yourself from panic. There are two ways. There’s an engineer who comes after the artist, but the artist has first to collect everything into the land of dream, to clear the way for the engineer’s thoughts.

And we find the way to our home. I am sure.

Simon Dove:

You have been listening to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and post-production is by me, Simon Dove, Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows, supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Simon Dove:

Hello and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I’m the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. For this podcast series, we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Amirah Sackett, based in Chicago, U.S.A.

Amirah Sackett:

My name is Amirah Sackett. I’m a dancer, choreographer, educator, and activist based in Chicago. I weave Islamic themes with dance in my choreography. The style of dance I do is hip-hop, in particular the West Coast style of popping.

To build a more equitable and just society, artists have stepped into a role of speaking out on issues that affect them or the communities they are in. That’s why I started doing my work We’re Muslim, Don’t Panic, back in 2011: to educate the public on misconceptions related to Muslims, in particular women in Islam.

The pandemic shaped the way we’re making art. Some people rose to the occasion. Others had to just take care of their life for a while, and their creativity will spark post-pandemic. I saw multiple things happening. One, artists embracing new forms. People that were stage performers taking to video. I learned a whole new way of putting my art out there, creating short dance films with my partner in the pandemic, Ahmed Zaghbouni, a filmmaker. It’s still a learning process for a lot of artists. These are some heavy times, and some artists don’t feel like creating super heavy work when they’re already depressed or down.

Aside from professional artists, what’s happening in society? During this pandemic, the rise of TikTok, of fun, short little clips that are entertaining. I compare that to World War I and World War II, when musicals skyrocketed. People wanted to escape reality. Right now some people want reflective art, and artists want to create that, and some just want to cheer people up and entertain them. People are gravitating towards things that make them happy and take their mind off of realities.

The West’s perception of women in Islam has definitely changed since I started my work back in 2011. Now we have Congresswomen who are Muslim. We have a lot more visible representation in the media. Muslim voices are being amplified, including Muslim artists. I was part of that movement, in 2011, where a lot of Muslim women were starting to vocalize their truths and starting to create. Now, personally, I feel like, yes, educating people of other faiths about Islam is a mission for me still, but more so it’s being subtle and letting my work speak for itself.

You can clearly see I’m Muslim. The themes in my work are universal truths and philosophies that are part of Islam, but I feel everyone can relate to. I’ve been interested in making work that touches people’s hearts in a way that they recognize that truth. Then secondary, they recognize that it’s coming from a Muslim voice, and that shows more of our unity than our differences. I would call it a more subtle approach. The title of my newest piece is Latif, one of the names of a law, and it means, the subtle.

I’ve done several virtual programs over the past two years. I was able to teach spring semester dance class at Harvard because it was virtual. That was awesome. A lot of arts organizations are struggling, definitely less work for me than pre-pandemic. Universities are not bringing in artists this year.

The Doris Duke Foundation, especially, has used their funds to support artists. I received a nice grant from them. The grant was about supporting artists so that they didn’t have to leave their art and take another job. There has been some great support from foundations, but it has taken a dive, and for a lot of artists, especially in the hip-hop community, it’s been difficult.

Using Doris Duke as an example, the shift in supporting an artist, and understanding that I’m not just supporting this artist to produce a piece, but to live so that they can produce pieces, that’s something I’ve never seen before, where it’s not like I’m giving you this money and then I want a product, it’s I’m giving you this money to support you, because I believe in you as an artist and don’t want you to struggle and worry about your basic needs. I hope that’s a shift that stays. I hope we can look at artists as valuable members of society that should be supported.

When you’re struggling to pay bills, you’ll be forced to produce art that wouldn’t be done as well as if you had your basic needs met. My creativity goes downhill because I’m focused on those things. When basic needs are met I establish a regular routine of creating, getting in the studio with other dancers, that’s when I’m soaring. I would love to see that shift in how organizations give funds to artists, to take into account that without a base of supporting artists’ livelihood, there won’t be great art. Of course, we’d have to really encourage artists to get better within their forms.

If you’re working a job every day, you don’t have time to practice your art. You don’t have time to elevate and hone your skills. It’s one thing being socially conscious artists; it’s another to be socially conscious artists who produce art at a high level. That’s my goal with encouraging the Muslim community, to work on their skills as artists. It’s not enough that you’re Muslim and you want to talk about it. The art that you produce has to be at a high level, and it has to compete on that world stage.

The pandemic has encouraged our artists to support each other, definitely. I’ve seen more collaborations than in a long time. I’ve seen dancers who never posted videos, never were really on social media, all of a sudden on social media. They’ve gotten attention from around the world that previously they hadn’t had, because they didn’t really have the skills or the time to invest in putting their art out there, or their dance form, on social media. Still, they’re not necessarily gaining a lot of income.

In particular, our older generation of artists, especially some of my mentors here in Chicago in the popping scene, we were able to, myself and my partner Ahmed, make a video for one of our legends. We helped him with that social media post. He’s in his 50s, he wasn’t super savvy with social media. After we did that initial, high-quality video, and he posted on Instagram, people went crazy. People that have seen him dance in person were so excited to see that level of quality in a virtual way. Since then, he’s really taken to posting on social media, and I’ve seen him grow his base and get new opportunities. That’s one way we’re supporting each other. Since I was collaborating with Ahmed, I was like, all right, who else can we uplift with your filmmaking skills? Who in my community can we work with? The current dance film that we created, called Latif, features also two members from my crew here in Chicago, who are not Muslim, but now are honorary Muslims because they’re in my piece. No, I’m just kidding.

I am optimistic for the future here, post-pandemic. Any time we go through a huge change as a society, we have to look back at it. We’re still in it, so it’s hard to know how things have shifted. I literally feel like I’m swimming in it. I have to get on the beach and look back at where I was, to understand how it’s changed.

One thing is for sure: the way we produce art has changed, and the way we interact with people, myself as a dancer, teaching Zoom classes, the possibility of using this to reach more people. Artists now can share things, and society is used to seeing it on Zoom. They don’t have to attend in person. That’s exciting. The possibilities are greater, reaching more people and new audiences. Connecting with artists across the world is being explored way more than before the pandemic. We will keep doing art projects virtually, for sure.

What’s nourishing me now, I’m working in Chicago with a team creating pop-up events in our Indian Pakistani neighborhood, a very famous street called Devon Avenue. I live a few minutes from there, where I get my halal groceries and things like that. Mainly it’s a street of grocery stores, small shops. There’s no art really happening there, no art museum, no events. Myself and a team, including Asad Jafri, who headed up this idea, he’s a cultural producer, and his wife Munirah, we’ve created these events. I love it. It’s getting back to my beginnings as an artist. We’re popping up on a street corner. We don’t have any permit from the city; we’re just making stuff happen.

We had an open mic last week, and the way the community gathered, and the interest, and the love: we had ladies leaning out their apartment windows to watch, people stopping in their cars, people grocery shopping and stopping to listen to poetry. It was incredible. This is feeding my soul, doing these events at home, and I didn’t have time for that before the pandemic because I was traveling, and I hadn’t been able to invest in Chicago. Right now, getting back to basics and doing something where it’s you and your friends coming up with ideas and just making a show happen, on a street corner, it’s giving me so much life. It’s so organic and beautiful, and it’s benefiting the community. That’s bringing me great joy.

Teaching classes in Chicago: I have two students who are 12 years old that have grown so much over the past year from taking class with me. Seeing growth even during this difficult time. Those girls give me life too, because they tell me stories about the school year. Everyone’s worried about the youth during this pandemic, and they just have me laughing and laughing about their funny experiences with wearing masks, and kids doing pranks on the teachers in Zoom classes. I’m like, they’re going to be okay. Me being in touch with the community directly through the youth and through my neighborhood has been really, really helpful in feeling optimistic.

Pandemic made you look at where you’re at, what’s around you, and how can I utilize it during this time to create. That was a big blessing and is a continued blessing. Out of anything negative that we experience, there’s always positives. There’s a lot to be thankful for even during this dark period of human history, but we’ll get through it Insha’Allah and we’ll be better than we were before.

Simon Dove:

You have been listening to The Future is Now, the podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and post-production is by me, Simon Dove, Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows, supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Simon Dove:

Hello and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I’m the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. For this podcast series, we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Selma Banich, based in Zagreb, Croatia.

Selma Banich:

My name is Selma Banich, and I’m an artist and activist based in Zagreb, Croatia. I think of myself as an artist that is trying to figure out how art practices can be a tool for social change. This is how I see what I do and how my art path is related or interconnected to my activist work. My practice is mostly about understanding and building relations. It has a material aspect, but it’s more. What I’m interested in is how art can build community, build relationships, or facilitate a process of voicing and embodying, and manifesting relations. And then community.

What works, or when my practice is making sense, or somebody else’s practice that I take part is making sense, is when it’s supporting the voices of people of the community, their agency, in a way that people—taking part in a workshop or art project or initiative, local or transnational—feel empowered by taking part. They are not only invited, but they are initiating and taking responsibility.

For example, this piece that I was speaking about that was commemorating, but actually condemning, the death regime being generated and executed by the European Union and nation states towards people on the move—migrants, refugees, and so on. The commemorative piece for the people who have died on their way to Europe through the Balkans, died in Croatian territory. The only way I could ever imagine doing something like that is by being locally embedded in my community, doing it with the people who had experience of that journey, who are here, who I’m sharing livelihood with, instead of generically addressing issues that I’m not in any way related or embedded in my local context. Otherwise I would feel I’m appropriating somebody’s voice instead of supporting it. And then using that to speak about something that is a global, planetary . . . not only situation, but like politics.

Kind of being put in this sweet spot where on one hand, you are curious about understanding what this practice can and should be for yourself, for your family, for your community, for this world, for the planet. And on the other hand, you need to also understand how to survive.

For me, the question is about how equality and equity and the social role that art has is interconnected with my personal responsibility as a human, and other way around. At this point in my life, this is becoming a very hard question. Because it’s the challenging times we live in, it’s really worth it, it has to be hard. And it is inviting me and all of us to kind of understand how and what is needed—more than how—what is needed to answer these questions genuinely and ethically, but also spiritually, just to yourself, but also to your community.

I’m referring to the last project I did with a group of woman from the collective Woman to Woman, the commemorative piece for the people who died on borders, because of borders, for example. That was very important that this commemorative piece, the practice of commemorating, and doing it as an art practice that was a collaborative communal process of a community and not individual person. So it is influencing a lot, of course, what I do, and how I do it, and with whom I do it.

On one hand, I feel there is a struggle amongst artists to survive this time, to build something that is missing and to offer each other that missing infrastructure and support. But for majority of us who are doing that, this is not a new thing. We do live that for 20 years, 30, 40, some of the more mature comrades. So of course there is this collectivity that is asking questions, how to rely on each other and rebuild what we need, by ourselves. But then also there is this notion of, it has to be a public responsibility. There needs to be a systemic solution. There needs to be a responsibility and solution coming from the system as well. Otherwise we would be talking about completely losing the notion of public culture that we had in the time of socialism and numerous other times, like with education, with health, with housing and so on.

So for me as a person who is inspired by anarchist philosophy and politics, to imagine sustainable autonomous solution, autonomous from the system, from the regime, it is compelling. It is something that I’m interested in, but also in the same time, I believe that there needs to be this pressure put on the system, on states that is addressing the state and demanding responsibility towards a functioning social services, where culture is one part of it of course, for me at least, culture and art.

In this time, we are also challenged to understand what is the material future of art? What do we choose? Do we choose producing art as any other commodity that then is going to be politically and materially and ecologically and socially and spiritually charged with one thing? So it’s going to be put on the battlefield as any other commodity that you get different kind of appropriations and manipulations, and capital basically runs the show. Or we want to see art as a tool that we as different communities and peoples are ready to use to make our lives better and prosper. And also as a tool to help communities and peoples to emancipate and work towards a better future.

And then my personal question is also, in this moment of obvious environmental crisis that we are living in, what do we want to produce? We don’t want to produce more commodity that will overload anyways, already. Art for decades is in over-producing hyper production.

Reminding the public that they have the right to have healthy, free, accessible culture. And I’m not talking about high art. I’m talking about art in every neighborhood, art in every community, art for all the people in a sense that you can become a practitioner. Bring a cinema in every village, bring creative workshops to all neighborhoods, bring art education in every community.

On the other hand, without having this opportunity to work also transnationally, to organize transnationally and travel, but also to learn from other communities and from other places on this planet, my embedding in my community would not be possible.

I still have some hope that by working locally or in a community in a local context, I can truly address the global political questions.

For me personally, I need to fall in love with people again, to again understand art from the perspective of desire. That’s for me really personal, because after 20 years of struggle, you get these moments where your hopes are kind of getting low. But at the same time, having hope or losing hope is also a notion of privilege. So I still have hope, but I also need to speak to my desires again, to find this vitality again, because that’s the only way, the grounds. That’s healthy grounds for human interaction and such, and also respect towards everything that is alive. So yeah, I’m calling in this desire for life or desire for art. And maybe globally, I would call in for fair wages for all that are based on ethical economies and decolonization. Political and economical decolonization.

I’m very much now into figuring out what pleasure activism or pleasure arts can be, or could be. I’m in a moment when, this is also very personal, where I want to learn about how to get back, not only the notion, but also politically, to take back.

Simon Dove:

You have been listening to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and post-production is by me, Simon Dove, Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows, supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Simon Dove:

Hello, and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I’m the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. And for this podcast series, we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Fatin Farhat, based in Ramallah, in Palestine.

Fatin Farhat:

My name is Fatin Farhat. I am a Palestinian. I am a freelance cultural manager, researcher, and evaluator. I’m based in Ramallah, but I work across the Arab region. In particular, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, also a lot in Egypt and with Syrians, not inside Syria, but outside of Syria because of the political situation.

Luckily, I’m not affiliated with one organization. I have been freelancing for the past six years. I work with multiple organizations, on different projects simultaneously. I try to balance practice and research because as a practitioner I used to manage projects on the ground. And research sometimes makes me distant; I miss the thrill of being on the ground. So in my assignments, I try to make this balance. I co-create and curate artistic projects that have connection to the community. I’m more interested in community-based projects. I also help Arab artists, Palestinians, Jordanians, and Syrians to manage their projects.

I advise funders who support the independent cultural scene in the Arab region and work with organizations like AFAC and Al-Mawred—I sit on the board of Al-Mawred—that act as intermediates between local communities and big funders. Artists and art-led initiatives are pressured by funders and organizations to work with communities because this is the trend. This is a bit risky because it tends to instrumentalize artists and communities they work with. For example, when you have a short scale project where artists are encouraged to work with the community, the artists work, they get out, and what happens to the community? No one asks these questions.

Many artists post Arab spring, in the region, felt for the first time that they have a duty towards their communities. Different projects like Fanny Raghman Anni, a Tunisian organization I work with, that do projects in streets, public spaces. There is the Ramallah municipality festival, Wein a Ramallah, which works with the community and encourages artists to create projects for the communities.

There is also a very interesting model I started working with called Sakiya, in Ramallah, an organization based in a village that helps the community and artists to reconnect to the land, creates artistic projects that are very localized and makes links with the environment. Artists should have a choice. The ambience is sometimes forcing artists to work in certain directions. The pandemic came as a surprise more to the Western world. In countries like Palestine, where we live in constant crisis, the pandemic is just another crisis.

I was overwhelmed because of the panic by my European colleagues who are not used to uncertainty, having to cancel events last minute, having little money to work with. Where I come from, this is the norm, not the exception. In Palestine in particular, the fragility of our cultural sector has been, ironically, a reason it survived and recovered in spite of the pandemic. Mobility in the Arab region is not easy. It’s easier for me as a Palestinian to get a visa, go to Europe, than to go to Lebanon. Relying on online platforms has encouraged many partners in the Arab region to work together without worrying about visas and so on.

We tried to mobilize to help artists during the lockdown. But there is little money anyway dedicated for culture in the region. There are issues of mobility, censorship. They were intensified by the pandemic, but just another in a series of crises our artists and practitioners have had to deal with in the past few years. For a big chunk of the Palestinian population that used to go to public events in person, especially in the summer, this has been a catastrophe, because they could not jump on these new tools as efficiently as the audiences that are used to going online to attend activities.

There was an advantage, but there was fatigue after a few months, not only in Palestine but across the world. Initially, everybody wanted and was excited to go online, but now a year and a half through lockdowns, people are willing to take a bit of a health risk and join an event instead of being online.

Even during the pandemic, there was a lot of focus on the sector as a whole, but not on individual artists in Palestine. Initiatives that were led by Al-Mawred, AFAC, and also Ettijahat and Action for Hope, creating emergency funds for artists, sick artists for the first time, artists facing legal difficulties—launching these projects created a debate in the region and made artists think of their own status. Because we don’t have active unions. The issue of pension, health insurance, artists struggle on the individual level.

There are no schemes to protect artists. Facebook posts by artists are calling for creation of unions. I see also organizations like Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Palestine creating a whole program that has to do with the condition of artists. This whole debate is motivating organizations and individuals to open up these questions. They are realizing that if they don’t work together, it’s difficult to survive.

One way of survival is to stand in solidarity with each other, look after each other. This is really vivid, really obvious, not only in Palestine but in Arab countries nearby Palestine.

Foundations in the region are interlocutors between big funders and smaller organizations. We have visions and future plans, but it depends on foreign funding of the organizations that support our organizations, our foundations. With very little exception—not speaking about the Gulf region—there’s very little local funding to the art sector in Palestine and many Arab countries. If you look at Jordan, Lebanon, maybe Tunisia, Syrians outside Syria: a lot depends not on our local foundations’ views, but on funders’ agendas.

Funder agendas change so rapidly for political reasons, thematic reasons. Sometimes funders are interested in women in the region, other times in environment issues. The fact that there’s no local public funding for culture makes it very difficult to think strategically. There is an organization in Lebanon now called Beirut DC that I’m working with on two projects. They decided to experiment with a new basic income project, give a chance for 20 filmmakers from the Arab region to have two years of basic income, so that don’t lose sleep over bringing food to their families, can focus on their projects. But how many funders are interested in this is another question; many funders feel it’s not sustainable. This issue of sustainability is becoming overused and abused in our region.

The wellbeing of artists is becoming a priority in my work, whether I work with a small organization to strategically plan, the issue of the artist fees, workers’ rights, health insurance, wellbeing as well. Two years ago, they were not so important to me as now. In my Ph.D. research, I changed my whole dissertation. I was working on decentralization of cultural policy in Palestine, focus on municipalities. I changed completely to governance of the independent cultural sector in the region, to see how artists are working and surviving. It’s unbelievable how drained artists are. Some just drop out of projects, and it takes us weeks to trace them, see where they are; they’re simply burnt out. Because they’re not properly compensated, work long hours, because there’s this argument that what you’re doing is good to the community so it doesn’t really matter if you as a mother are ignoring your kids, not taking time off. These issues have made me, in fact, reshape my research.

Lately cultural organizations realize they have to open up to other sectors. So now projects involve human rights organizations, women’s organizations, environmental organizations. A project I’m working on with Beirut DC is called Dealing With the Past. In Lebanon, the past is a very heavy issue: civil war and disappearance of 17,000 Lebanese. No one knows where they are. This project invited civil society organizations, not only cultural and cinema organizations, to think of how to come together, work artistically with communities, and deal with this difficult past of Lebanon. This ultimately leads to a bigger audience, because each sector has its audience as well. This is one of the best ways for the cultural sector in our region to be acknowledged by bigger communities: through bigger partnerships with other civil society organizations.

We have a project called Stand with Art, dedicated to artists under threat, to get Arab artists out of the region. We try first to relocate them in the Arab region then it’s impossible. These exchanges are very important at creating safe haven for artists to go up north. But that’s also problematic because most of the transnational cooperation is Eurocentric. Because again, that’s where the money is. We see less cooperation between the Arab region and African countries, or with India. Normally when we speak of transnational, it’s Arab European. I see it all the time. And again, that’s because the cooperation follows the money. We are trying to create schemes in the region that encourage Arabs to work together but also encourage artists to work with Central and South America. This needs fundraising, again.

In the last 10 years, we witnessed the emigration of many Arab artists to Europe. Berlin, for example, is becoming the new hub for Arab culture. There has always been Arab artists living in Europe, but the numbers have significantly increased post Arab spring. So we have to be very sensitive when we speak of north-south in that definition; I’m not sure that the definitions are valid anymore, since many artists are already making a living in Europe.

In general, I’m a pessimist, but I get waves of optimism. Artists and practitioners are more aware of their rights, more willing to negotiate for them. The problem is that we need frameworks to help them work collectively. Personally, this is the responsibility of someone like me who is more of a manager, has a general view about the sector, comes from a union background, has connections to organizations. We have to capitalize on this knowledge and desire that artists and practitioners have, help them with frameworks, because, you know, artists hardly have enough time to survive, to create, to also worry logistically about this layer.

Almost every employee in Palestine has health insurance, whether it’s good, public, private, premium [inaudible] and workers. We had a case last year of an artist diagnosed with cancer. He had to mobilize friends to pick him up and pay for his medical care. This should not be the case. In any other organization, the NGO would’ve paid his medical bill. Independent and freelance artists don’t have this. We need to, as practitioners and managers, researchers, organizations, lobby for public funding for art and culture in the region. It might be difficult in some countries, but it’s definitely possible in countries like Jordan, Palestine, Tunisia. We have different governmental structures, but it’s possible if we are better organized.

Arab cities are changing and demanding cultural management. In Ramallah I started this issue of what became the decentralization of public cultural policy. Amman is another example, capital of Jordan, different cities across the Arab region that have said, enough, we have a mandate towards our community in cultural development. We need to advocate for that because, to be honest, cities are much more democratic. I’ll give you an example. In Palestine, we haven’t had legislative or presidential elections for 10 years, but we have regular local elections. It’s a democratic tool that we as artists have to capitalize on.

We need also to negotiate with big funders, to open discussions. Because to have more equilibrium in the relationship, of power, between us and funders, it’s very difficult to do that. But as coalitions in the region, we might have some power on deciding our priorities, rather than funder priorities. At least engage in a process of dialogue. We need to encourage artist-led initiatives, to be more flexible with governance structures. Many of the available or adopted governance structures are so strict and limiting. We need to invest in art education, which in many of our countries is almost nonexistent. This is really horrible in terms of artist empowerment and community empowerment.

As people working in the independent art scene in the Arab region, we have to challenge what it means, the terminology itself: What is the independent Arab scene? What is it independent from and why is it independent, and when should it not be so independent? This is the first thing we have to do. This is making it very difficult to advance the sector because it’s so diverse, so many different artistic disciplines and political realities.

The other issue is, we need to explore flexible governance structures; many organizations are doing that on the ground. Even classical civil society in Arab region is becoming very hegemonic, acting like the government. We want to mobilize a different way, engage more with communities, in longer conversations that are not as efficient—if you wish—but more relevant to the communities. We need to identify these initiatives, work with them, try to understand them, and encourage other artists to learn from them.

Simon Dove:

You have been listening to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and post-production is by me, Simon Dove, Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Simon Dove:

Hello, and welcome to The Future is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove, the Executive Director of CEC ArtsLink. And for this podcast series, we asked 10 independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from curator Elena Ishchenko, who’s based in Krasnodar, in Southern Russia.

Elena Ishchenko:

My name is Elena Ishchenko. I’m a curator and researcher based in two Russian cities, Moscow and Krasnodar, a city in the south of Russia, and I work as a curator and manager in Typography Center for Contemporary Art. It’s an initiative which goal is to create and open an inclusive platform for dialogue and provoking discussions, supporting communities and developing contemporary arts in the region, in the city. As a researcher, I’m interested in self-organized art initiatives and collectives, principles of their work in theory and in practice, and infrastructures of contemporary art in Russia, especially in non-capital cities.

It’s really great feeling that working in self-organized initiatives and communities gave me. So as a researcher, I started to explore these self-organized art initiatives from 2014, and the main point about these collectives and initiatives, the organization, is all of them are based on collectives. And the history of art and initiatives is more about individuals. It’s super important to imagine all of this process, the collective, because now, pandemic shows us that collectives and collective solidarity is important for our days.

Always have weekly meetings to discuss our events, our activities, but also we try to discuss our ideological principles and basics. Some weeks ago I realized that every institution and organization can be structured in another way. Every museum can be horizontal and without hierarchies, and be governed without departments and so on. This is the examples, these self-organized initiatives can show that everything can be organized in another way.

The Typography Center for Contemporary Art I work in, is a very good example of such kind of initiative. Another one I really appreciate and admire is Moscow International Film Festival, which was organized by Vladimir Nadein, a director, manager, and producer. But last year they decided to restructure their organization and start to work as a horizontal initiative. It’s very brave experience, but the same time, the festival, which held this year in August, showed that it can work perfectly without any director.

It’s very important not to see this self-organization as a main goal, because we should not forget the principles, and our dreams maybe even, what world we want to live in and how it should work, how all the structures and infrastructures should work. Sometimes it’s really very inspiring that you can behave yourself as you already live in this imaginary world. But at the same time, sometimes it’s frustrating because you still live in this world.

Any self-organized or horizontal organization, you are more open and attentive to others and more attentive to what surrounds you.

This term is inclusiveness, yes. Artists and maybe institutions play really important role in this process, and the strategies of art institution are very important here because they should be more inclusive and provide equal opportunities for different artists and participants of the process.

And not only for star famous, recognized artists, but for everyone, to be more attentive to local context and explore what’s going on, and what artists live and work around your city, your neighborhood, et cetera. This question of quarters, which is really urgent now, it’s important to keep in mind. It’s not only about men, women, artists balance in your project, but we also need some, imaginary maybe, quarters for artists with children, artists from indigenous people, and who lives and works in non-capital cities. Every time we are making some projects in Typography Center, we always think to include artists from non-capital cities, and our city and region, into the project. Maybe it’s easier to find budgeting and money for projects with famous artists, because these events will have better media coverage. But what is really important is to create these inclusive platforms and events and projects.

I see in Russia this division between what institutions doing and what artists and independent curators and small institutions really need, and there were very great discussions last year around the NEMOSKVA project, organized by Alisa Prudnikova. It was always about representation of the regional artist, and that’s one of the main topics there: every artist in regions need this big project to be represented, to be visible and so on, so forth.

But is it really the thing that art needs? There are lots of artists, and of course there is this career that we see as something we should relate to, that you should graduate from school, then you should sign a contract with a gallery, then you should do a museum exhibition, then you should go to Venice Biennial. And this is like a prominent career of the artist. But of course there are lots of artists that do not want this career because they just want to do their project, want to live in interesting surrounding, and want to work and have some relative payments for their work. This is really more important than this big project, this international visibility and so on.

Unfortunately now in Russia, lots of these things we should do by ourselves, so it’s self-organized, and one of the important initiatives, that were again started to discuss during the pandemic, is the basic income. This discussion was initiated by a performance artist and dance artist, because their work is most immaterial, and they do not have object to sell in art fairs or show in galleries. If we cannot gain this goals as basic income, we still should talk about it, to make it closer.

Yeah, this system should be transformed. What is important is to make our desires more visible for this system. Because of course, pandemic shows that art market system, and this system of big institutions, doesn’t work for everyone. It’s super exclusive. It creates possibilities only for few, few, few artists and for few curators and few researchers. If you want more sustainable and just society, we should reimagine it and create another platforms.